Beyond ‘Almost Famous’: Cameron Crowe shows his ‘Uncool’ side in memoir

Loading...

If you’ve seen the 2000 film “Almost Famous,” you might think you know Cameron Crowe’s story. But in his memoir “The Uncool,” the wunderkind music journalist and Oscar-winning screenwriter and filmmaker dives deeper into what he calls his “happy/sad” Southern California childhood. And his book gives readers a backstage pass to his interviews with rock music legends. It’s a riveting memoir right from the start.

Crowe’s father, James, from Kentucky, was a rising star in the U.S. military; his mother, Alice, was a schoolteacher from California known for her love of philosophy and aphorisms (some of which serve as chapter titles in “The Uncool”). During Crowe’s childhood in San Diego during the 1960s, Alice insisted that he follow in his great-grandfather’s footsteps and become the youngest lawyer in the country. Crowe graduated from high school at age 15. However, he notes, “skipping grades in these key adolescent years would create serious land mines in my life.”

Crowe’s love of music, from Led Zeppelin to Marvin Gaye, set him on a much different path from law. Alice railed against rock music, finding it “inelegant” and “obsessed with base issues like sex and drugs.” She urged him to stick with their plan, telling him, “There’s no room in the world for a thirty-year-old rock critic.” She eventually changed her mind, thanks to concerts by Bob Dylan and Derek and the Dominos, but until then, Crowe found supporters in his older sisters Cathy and Cindy, who supplied him with a steady stream of record recommendations. They also coached him through awkward, “uncool” childhood.

Why We Wrote This

Golden-era 1970s rock music forms the soundtrack for many people's lives. As a young man growing up in Southern California, Cameron Crowe carried that passion into interviews with rock's biggest names. When rock yielded to punk music, he switched to screenwriting and moviemaking.

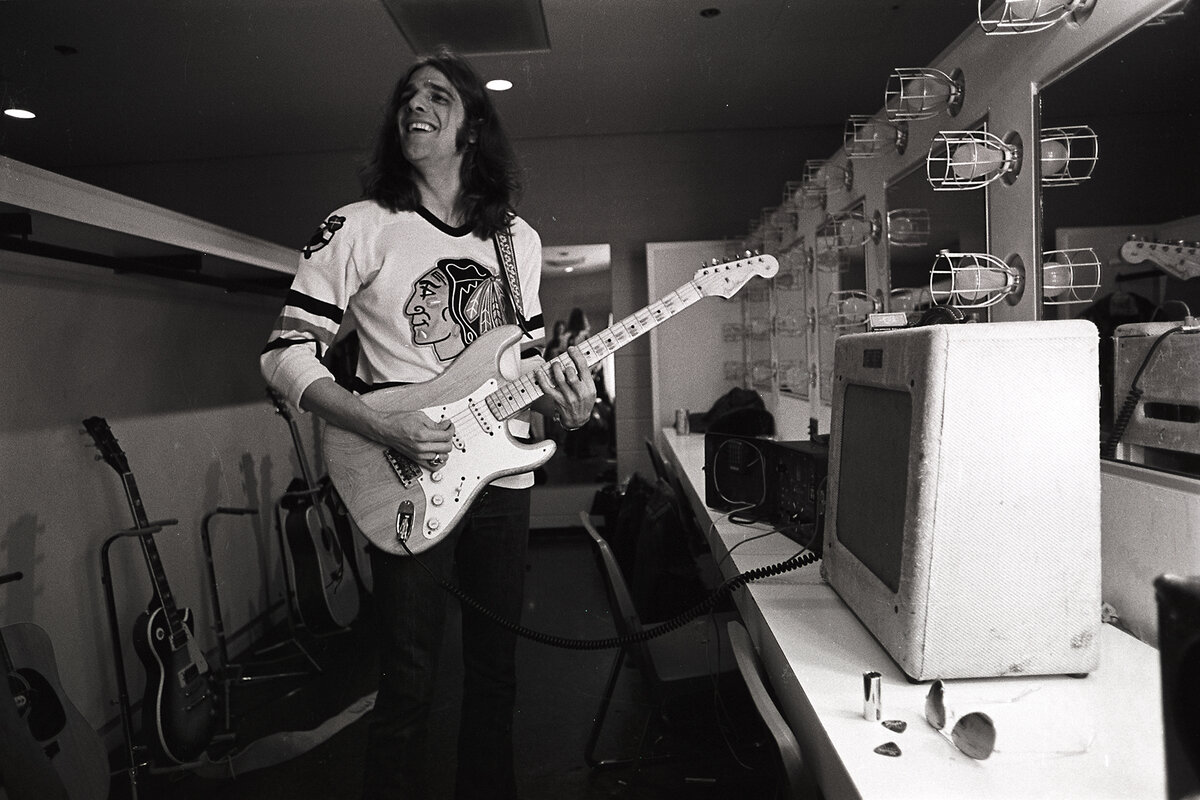

By the time he turned 15, Crowe was writing record reviews for San Diego’s local underground paper, the Door, before moving on to interview the giants of ’70s rock: the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, Van Morrison, and Black Sabbath, to name a few – for Creem and Rolling Stone magazines.

Crowe encountered a number of obstacles because of his young age. Interviews overlapped with summer school classes, and he was hampered by the lack of a driver’s license. More crucially, many concert venue owners and bouncers refused to let him inside for fear of losing their liquor licenses. Despite these challenges, Crowe found musicians and music journalists willing to give him a break. Kris Kristofferson once attempted to bribe a maître d’ to let Crowe into a cantina for an interview, for example.

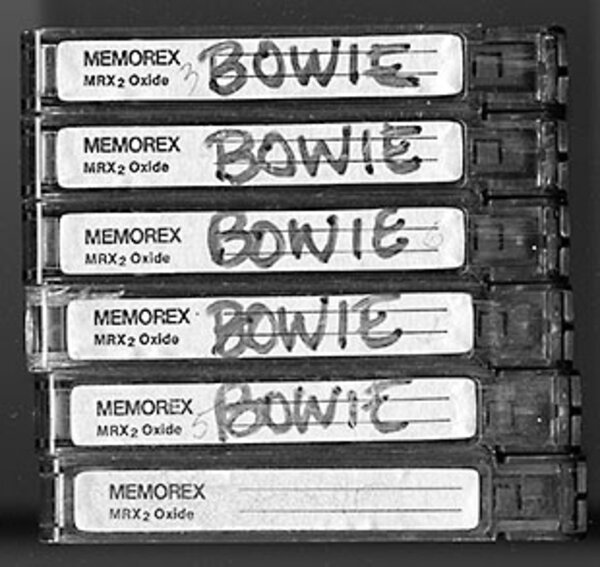

When Crowe encountered the press-elusive David Bowie at a party, they bonded over the Spinners. Bowie allowed Crowe to follow him for 18 months, eventually handing over the first 12 pages of his autobiography. Why? Because Crowe was, in Bowie’s words, “young enough to be honest.”

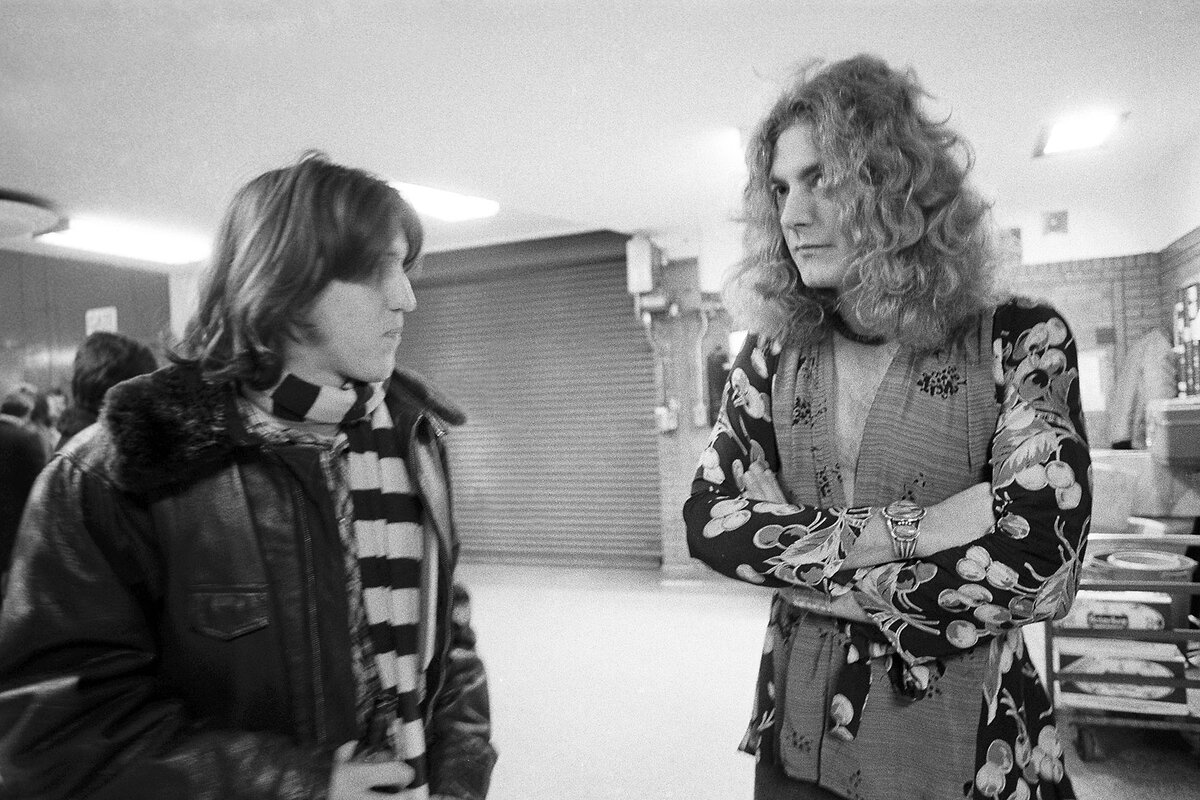

It’s this honesty and humility that gains him interviews with Led Zeppelin and Joni Mitchell after they’d sworn off Rolling Stone, and even more apparent in his interview with the Allman Brothers Band in the wake of founder and guitarist Duane Allman’s death.

For Crowe and his sisters, “music was an emotional beacon” with “happy/sad” songs from artists including Mitchell, the Beach Boys, and Todd Rundgren – songs that sound upbeat but are also melancholy. When Crowe was 10 years old, his 19-year-old sister Cathy took her own life after a long struggle with mental illness. He found solace listening to the Beach Boys singles he and Cathy had ordered just before her death, and Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”

After years spent following bands on tour, Crowe returned to San Diego in 1977 in a rut. Gone were the days of rock; punk music had taken the mainstage. Rolling Stone bypassed him on story assignments. Members of Lynyrd Skynyrd – with whom Crowe was close – died in a plane crash. At just 21, Crowe told his parents he was “washed up.”

The return to his family home and to a kind of adolescence proved to be a turning point. Crowe went undercover at a high school to write “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” first as a book, then as a movie script. Wistful coming-of-age films including “Say Anything” and “Almost Famous” followed.

In “The Uncool,” Crowe embraces the “happy/sad” – finding home somewhere in the balance between the two. It’s a place readers can appreciate, too.